The Four P's That Connect the World

Products, payments, people, and pollution

Photo credits: Chris Linnett, Jason Leung, Daniel Schludi, Billy Joachim

Most of us have a worldview that is more like a localview. In many ways, this is understandable: we are more likely to see things that are physically close to us. Each of us has to to construct a mental model of the world based on the highly skewed sample of data injected into our ears and eyes.

Even so, places beyond a person’s immediate locality often makes it into their worldview. Not just Michigan but also the United States. Or not just the United States but also Canada, Europe, Japan, and Australia. Sometimes places like China, Iran, or Israel and Palestine make it in there too. But that still leaves out three-quarters of all humans—for those of us in the Global North, the way we think about the world often excludes the hidden majority living in the Global South.

In a world as interconnected and unequal as our own, we need a worldview that genuinely extends to the world. When you look beneath the surface, every human’s local reality is being shaped by actions taking place on the other side of the world.

The global movement of four things connects where you live to every other place in the world: products, payments, people, and pollution. No part of the world is untouched by them. No border can fully isolate a country from them. You might not see any evidence of your connection to places like El Salvador, India, and Vanuatu, but every day the Four P’s move between your world and theirs.

We live in an inextricably interconnected world. Whatever you are trying to achieve—fairness, security, prosperity—you will be led astray unless you understand that.

Let me explain how the Four P’s connect the world, before some thoughts on why the MAGA nationalists trying to cut ourselves off from the world are doomed to fail. As you read through, you might start to get overwhelmed with all the big numbers and different ways distant parts of the world connect. That’s kind of the point—we live in such a mindbogglingly interconnected world that the examples go on and on.

Products

You probably have dozens of products near you right now. Look at their labels and see where they were made. The iPhone in my pocket was made in China. When I look to my right, I see my partner’s coffee machine (I don’t use it personally because coffee is disgusting). The machine was also made in China. The t-shirt I’m wearing was made in Honduras, while my shorts were made in Jordan. Those are all middle-income countries, with GDPs per capita between $7,500 and $27,000 (when you adjust for differences in prices between countries). That’s not a coincidence. Apart from high-tech products like semiconductors or MRI machines, most manufacturing is done in countries where incomes are very low by Global North standards but still higher than in the poorest countries in the world.

An iPhone manufacturing facility in Shenzhen, China.

But even if those are the places where products are assembled, they are typically depend on materials from elsewhere. My iPhone’s battery uses cobalt, a large majority of which is mined in the DR Congo. The top producers of coffee are Brazil, Vietnam, and Colombia. For the cotton that goes into clothes, 12% of global production is in the United States, but China, India, and Brazil grow more. In comparison to where manufacturing takes place, these materials come from a wider range of countries. Quirks of geography and climate determine which countries have which commodities, so you will find high-income countries like the US that produce lots of cotton, soy beans, and oil and gas. But you will also find commodities concentrated in very low-income countries: the DR Congo’s price-adjusted GDP per capita is just $1,700.

An artisanal cobalt mine in Luabala, DR Congo.

Services are more likely to be provided locally than goods (you can’t cut my hair while located abroad), but many services are also exchanged globally. Call centers represent the most recognizable example of this—when you call for customer service, there’s a good chance someone in the India or the Philippines will pick up the phone. If you report a social media post for violating platform standards, someone in countries like the Philippines or Kenya will review it. Everything from preparing your taxes to reading your MRI might be done by someone in India or Colombia.

A call center in the Philippines

All this is a huge change from how people historically lived. International trade has been around for millennia, but until a few hundreds years ago it was still the case that almost all products people used were produced locally. Trade began to expand during colonialism (on coercive terms) and—after a period of retrenchment in the first half of the 1900s—has now exploded. This globalization has important distributional effects for production (making t-shirts in Bangladesh can replace jobs that were done by working class people in Boston) but it also has important effects on consumption (the lower wages paid to Bangladeshi workers mean a Boston electrician can buy cheaper t-shirts). Still, many shifts in inequality are down to factors like automation, tax policy, and social benefit policy more than trade.

After decades of expanding global commercial networks, we have become accustomed to the results—affordable iPhones, coffee at the grocery store, and MRIs evaluated overnight—but still have little awareness of where our products come from.

Payments

Having covered the global movement of goods and services, let’s move on to the global flow of money. A quick reminder to start—there are various types of payments. We tend to think of paying for products: I pay you money, you give me something. But much of our economic system depends on a different type of payment: I pay you money now, you pay me money later.

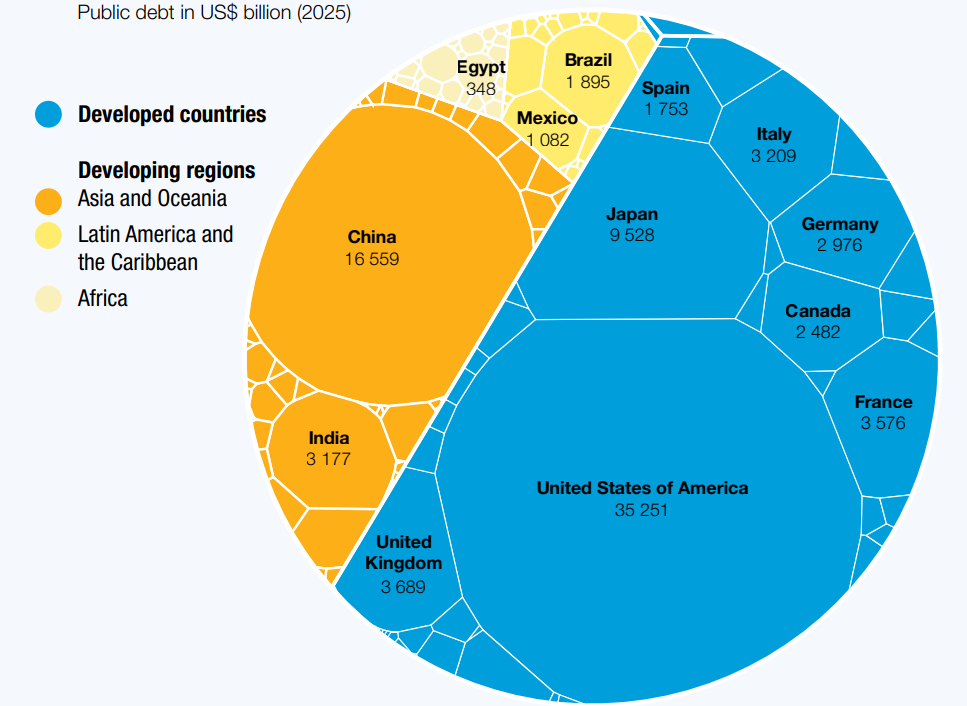

Like trade, finance is highly globalized. Let’s assume you have a 401(k) where you put your savings for retirement. That money is going to be invested, and it is virtually guaranteed that some of those payments will circulate around the world. If your money was invested like the average American, roughly half would be invested in the stocks of US companies, though those US companies often operate internationally—remember how much of the production of Apple products takes place outside the US. A smaller share will be invested in the stocks of foreign companies. Another segment of your money would be invested in bonds, a majority of which are issued by governments. A lot of that comes in the form of US treasuries, but US government debt is still a minority of global public debt.

Global government debt in 2025—some of which is probably in your 401(k)

So if you are investing money, a good chunk of it is probably circulating internationally. But what about if you need investment? Here, the exact depth of dependence on globalized finance depends on two sometimes contradictory forces. In general, when you are in a place without much money, you are more likely to need financing from abroad. If a Tanzanian trucking business is trying to expand its fleet of trucks, there aren’t that many people in Tanzania with large sums of money to lend out. Likewise, if the Tanzanian government is trying to build a road, there isn’t much wealth in Tanzania to tax. In the US, it’s easier to get financing from domestic sources, so it’s not as essential to look abroad.

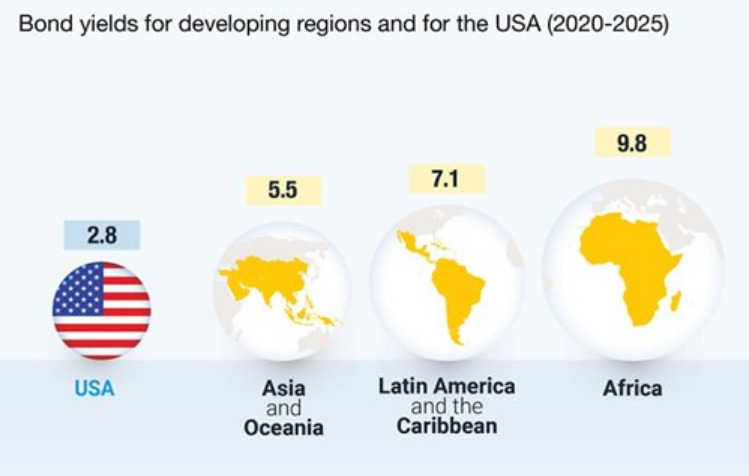

But on the other hand, the further down the economic food chain you are, the harder it is to get financing from abroad. The Tanzanian company and the Tanzanian government would only be able to borrow from international sources at high interest rates, generally in a foreign currency and with short payback periods. In contrast, even though there is plenty of money available in the US, there are also plenty of people abroad who want to invest in the US and are confident they’ll get paid back, so they’ll provide this financing at low interest rates. Indeed, US Treasury bonds are seen as the safest assets around (though it’s possible that is changing), are there is huge foreign demand for them.

When African governments borrow internationally, they have to pay interest rates that are on average four times higher than the US government.

And I still haven’t touched on a whole series of other ways that money moves around the world, with people and companies in the Global North holding disproportionate power. There is governments’ taxation of the foreign companies operating in their territories, and all the payments those companies route through tax havens to avoid paying taxes where they operate. There is international humanitarian and development aid, which amounted to over $200 billion per year before the huge cuts this year. Hundreds of billions of dollars also flow to developing countries each year from the International Monetary Fund and multilateral development banks like the World Bank. This money typically comes as loans with better terms than those countries could access from private lenders—but decision-making power lies not with the countries where that money will be invested, but by governments elected by people like me. Most voting power is held by developed countries, and the US is the only country to hold a veto.

There’s one last vital global dimension to payments worth remembering: it matters which money you are paying in. Global demand for your country’s currency—whether for buying products, borrowing and lending, or otherwise doing business in your currency—will push up the value of your currency relative to other countries’ currencies. When your currency gains value, it becomes easier for you to buy things from other countries but harder for them to buy things from you. (Good news for consumers but bad news for many factories.) And because the US dollar is the world’s go-to currency, effectively serving as the monetary equivalent of a “lingua franca” for the global economy, it means US policy decisions—particularly by the Federal Reserve—have outsized global impacts.

People

In some ways, there is less global movement of people than there is for products and payments. 96% of people live in the country of their birth, and 80% of people have never been on an airplane. Still, nearly every country is meaningfully shaped by the movement of people. If you live in the US but don’t trace your heritage to Native Americans, travelled internationally this year, or ate a taco or curry this week (and aren’t from Mexico or South Asia), you can understand why.

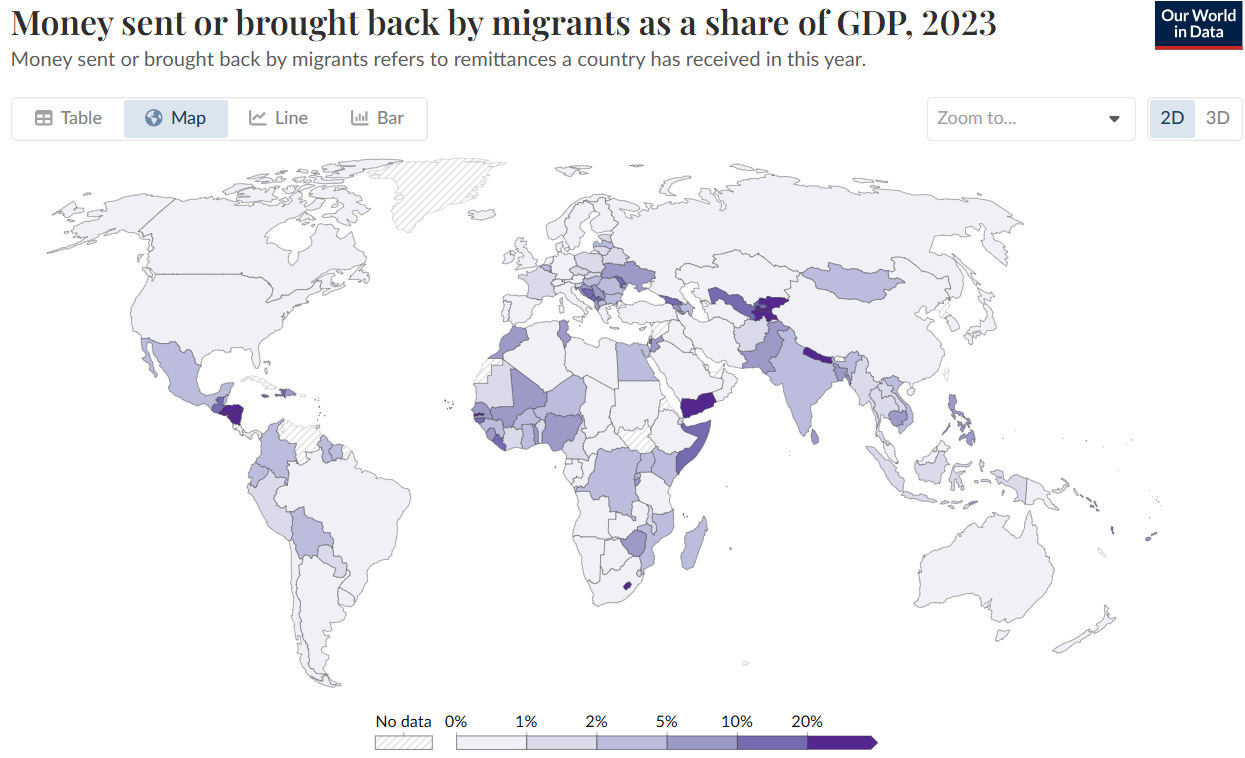

Even for the large majority of people who stay in their home countries, migration has enormous impacts. More than a quarter of Africans, Middle Easterners, and Latin Americans want to move abroad, even if they don’t end up doing so. Money sent back by people abroad has huge financial implications: each year, developing countries receive more than three times as much in remittances as international aid. Likewise for money spent by people visiting: 25 countries get more than 5% of their GDP from tourism.

For Yemen, Nepal, and several Central American countries, money sent back by people abroad makes up over 20% of GDP.

Let’s get a few basic facts in our head about the global movement of people. When people move—for better economic opportunities, to join loved ones, to flee conflict or climate stress, or any other reason or combination of reasons—they are more likely to move within their country than to move abroad. Of the people who move abroad, only around 15% are refugees or asylum seekers (though in reality the line between refugee and “economic migrant” is quite blurry). There are way more people in the Global South than the Global North, so it is unsurprising that—as a matter of quantity—most people moving around the world are from the Global South. But because travelling costs money and people in the Global North tend to have more of it, they are disproportionately represented among international travelers.

When people leave Global South countries, it isn’t just for the Global North. There is slightly more South-South migration than South-North migration. And Global North countries only host one-quarter of the world’s refugees. If the US hosted as many refugees as Lebanon relative to the size of its population, it would host 87 million refugees, double the total number of refugees in the world. All of this to say is that the immigrants we imagine—moving from a poor country to a rich country, perhaps via a dinghy or smuggler’s truck, fleeing violence and/or seeking asylum—are a very small share of all immigrants.

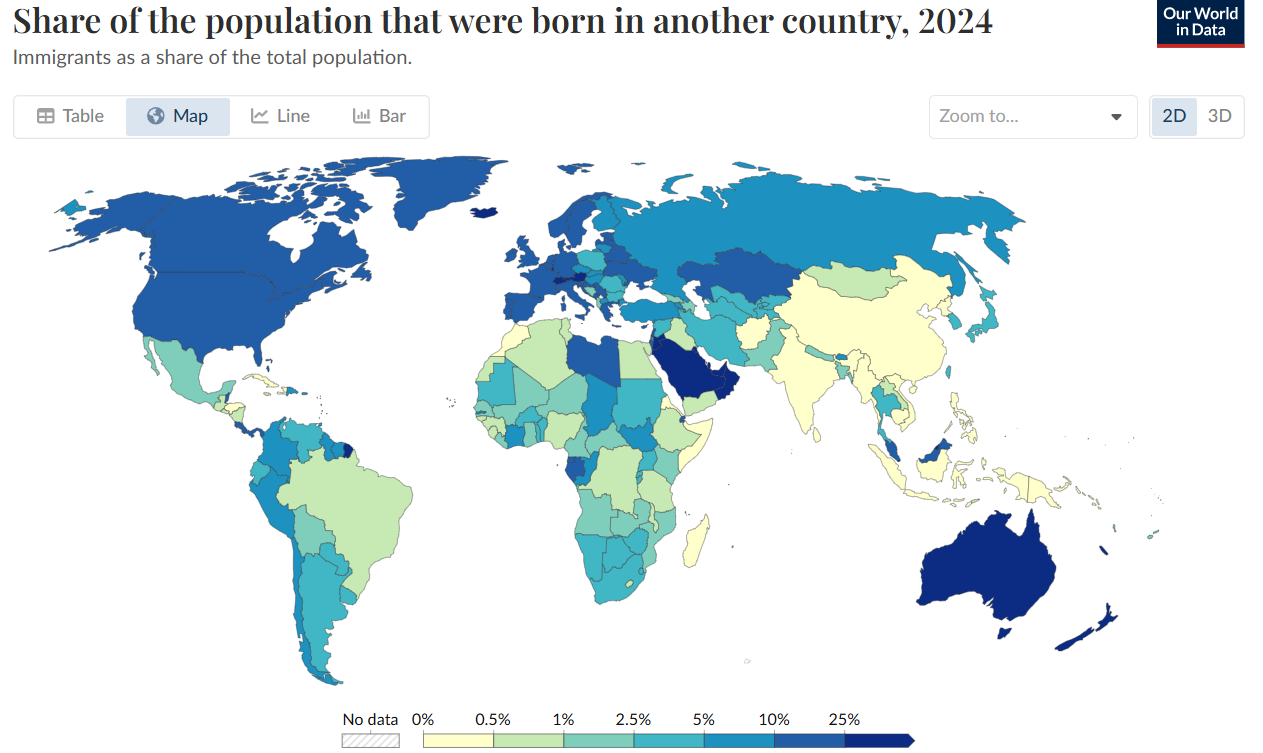

Still, people generally want to move to richer countries, and it is true that people born abroad make up a significant share of many rich countries’ populations. In the US, one out of every six people were born abroad. That number is one-in-five in Canada and nearly one-in-three in Australia. The highest levels of migrants per capita can be found in Gulf countries that have become major destinations for Global South migrants (though once they get there, immigrants often have severely limited rights). In some such countries there are more than three foreign-born people for every one native-born person.

Darker blue countries have a larger share of their population born in another country.

Rich countries do not only have a higher share of immigrants because they are richer—it is also because they are older. As I wrote about here, the Global North is much older than the Global South. Barring the raising of retirement ages, a sudden proliferation of robots, or a baby boom (and even that wouldn’t produce workers for 20+ years), the only way to get make up for the decline in a country’s working age population is to have new people come from abroad. If countries fail to take up that option, the consequences can be easy to miss because they are gradual. But they sure matter: slowed economic growth, reduced housing construction, elder care worker shortages, and more.

Pollution

Some of the global movement of pollution comes in the form of the physical pollution we are accustomed to thinking of. A significant share of rich countries’ trash is sent abroad—much of that went to China until China banned waste imports, and now it is sent to an wide range of Global South countries (and of course some ends up in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch that’s three times the size of France). There is also localized pollution that results from international economic relationships. In the DR Congo, cobalt mining that ends up in batteries used abroad has produced acidic waste that has poisoned people and crops. Some of the cities that host the most factories producing goods for Western consumers are covered with thick smog.

Smog in Sialkot, Pakistan, where 70% of the world’s soccer balls are manufactured.

But it is pollution of the atmosphere that has the greatest global impacts. By this I mean greenhouse gases—chiefly carbon dioxide, but also gases like methane and nitrous oxide. When these gases are burned, they rise up into the atmosphere and begin to circulate as part of a giant, heat-trapping blanket that functions like a greenhouse. Because our atmospheric system is delicate and highly interconnected, the effects are wide-ranging: not only does trapping more heat increase average temperatures, it causes glaciers to melt, which causes sea levels to rise and the flooding of coastal areas. Warmer temperatures accelerate evaporation, exacerbating the dry conditions that facilitate wildfires.

Here, the level of global interconnection is basically 100%. Greenhouse gases emitted in Saudi Arabia, China, or Indonesia affect the climate you will experience just as much as emissions coming from down the street. Of course, not all parts of the world are emitting equally. Some greenhouse gas emissions are produced by land use changes like deforestation, but most emissions come from the burning of oil, gas, and coal for energy—to fuel cars and planes, to heat and cool buildings, and to provide electricity for anything we plug into a wall. Because richer people consume more energy, richer countries have produced more emissions (and within every country, its richer citizens emit more than its poorer ones). But the extraordinary advancements in renewable energy mean that it is now possible to decouple material prosperity from emissions—powering cars, heating buildings, and charging phones can be done without any emissions as long as they are powered by a renewable source.

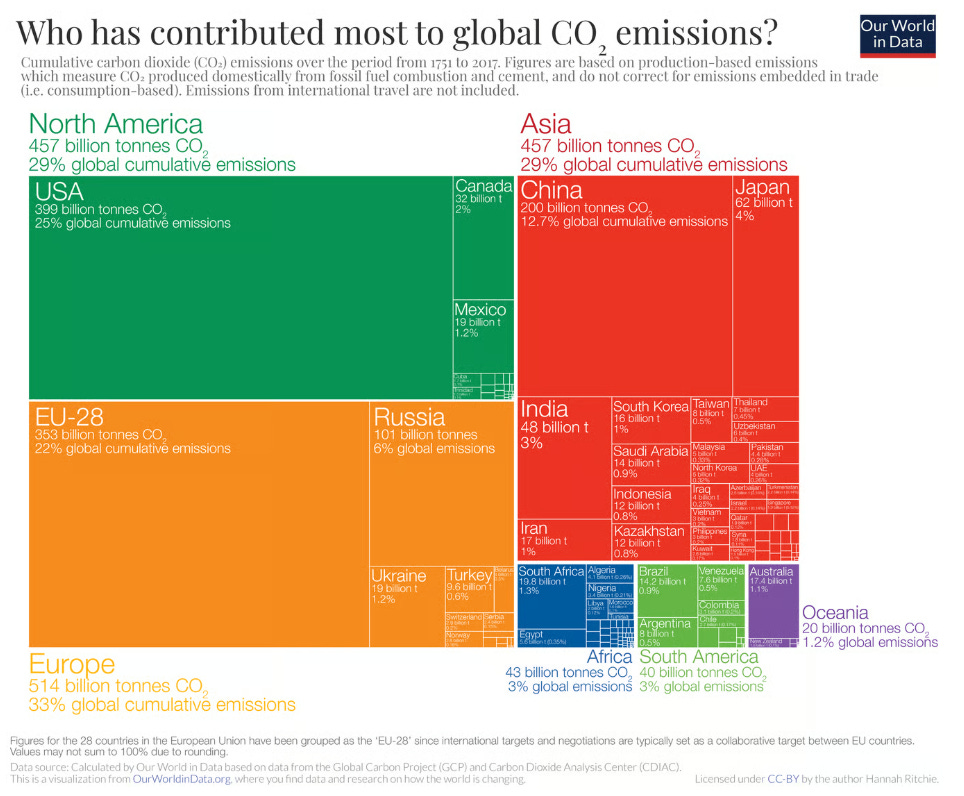

A (slightly out of date) breakdown of where all the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere came from.

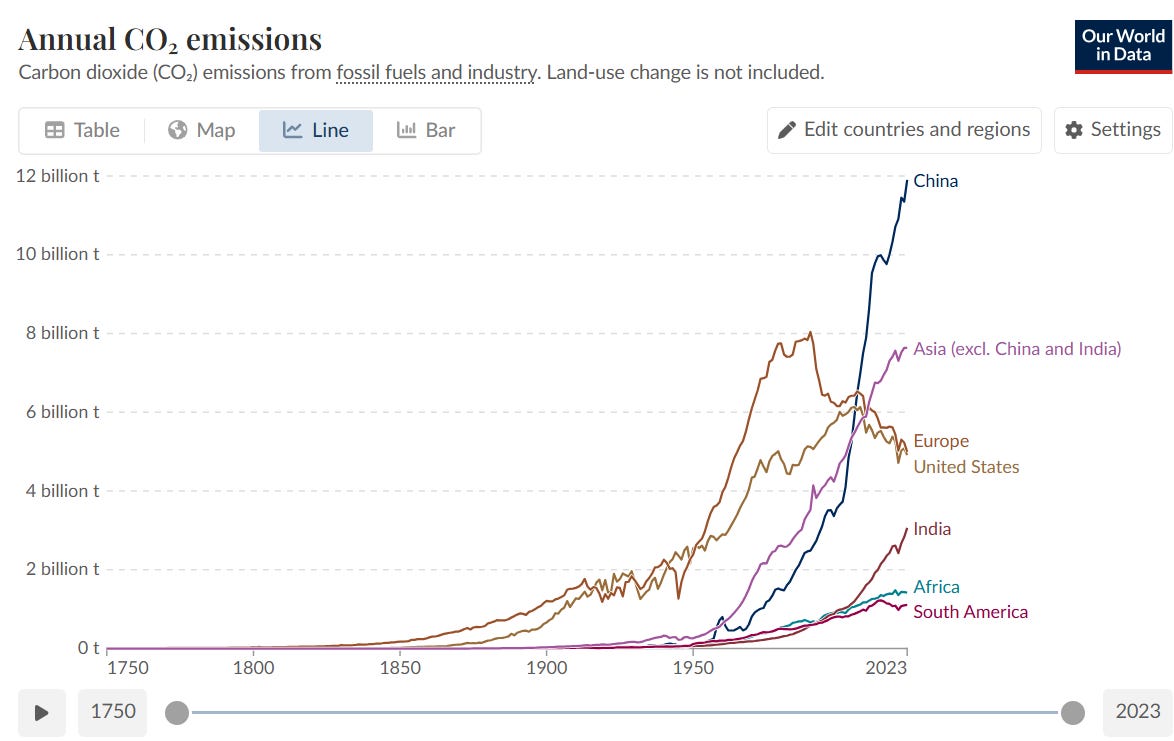

In the present, the emissions picture looks different from the past. About one-third of emissions come from rich countries, which still emit disproportionately to their share of the population but are generally reducing their emissions (especially Europe). Another third of emissions come from China, though it has also become the world’s leader in the production of renewable energy technology. The last third of emissions—and the fastest growing share—comes from developing countries. Renewable energy offers them real opportunities, but they face the greatest constraints: they still need to significantly increase their energy consumption so that citizens can get their first cars and fridges, and the challenges highlighted in the Payments section above make it hard for them to finance renewable energy investments that demand a lot of money up front.

Annual carbon dioxide emissions by country/region—see 2023 on the right-hand side of the chart for the most recent data

What all this means is that climate change in the final, decisive step towards a world of inescapable global interconnection. For most of human history, societies lived in isolation, with no knowledge of each other’s existence nor any way to influence distant bands of humans even if they wanted to. But now, even the most isolated communities in the depths of the Brazilian or Indonesian rainforests—those who avoid all contact with outsiders—are inextricably bound to their fellow humans. They can see the United States’ fossil fuel-powered rise in the wilting of the leaves. They can witness China’s coal-powered development in the capriciousness of the rains. They will feel the speed of the Global South’s take-up of renewables in the tolerability of the air’s humid embrace. In our world, you do not need to see humans to feel their impacts.

What the Four P’s Leave Out

For one, nuance. Global interconnection is so deep and sophisticated that any framework is going to rely on some simplification. Most sentences in this blog have had a whole book written on the subject, and I know there is a lot of nuance that didn’t make it in.

But there are also a few forms of global interconnection that arguably deserve their own “P.” First, pandemics. As the COVID-19 pandemic showed, a virus can quickly move around the world. Especially because current conditions exacerbate the risk of pandemics starting and spreading, public health in any country is closely tied to public health internationally. Strengthening global systems to detect, treat, and vaccinate against pandemics is a core shared interest.

Second, the Four P’s don’t really touch on security and war (perhaps the “P” would be projectiles?). Interstate conflict does of course have huge effects on the countries involved, and countries go to great lengths—foreign military bases, arms sales, undermining foreign governments—to try to strengthen their national security. Nuclear war of course would have even more dramatic global effects.

I tend to think that in comparison with the Four P’s—which travel between every country every day—the global impacts of pandemics and projectiles are more limited to certain moments and geographies. Pandemics and violent conflicts have huge effects when they happen, but most of the time there isn’t a pandemic affecting more than a few hotspots, and most countries aren’t at war. I could be convinced otherwise, though.

One could also make a good case that knowledge, culture, and ideas deserve their own P—technology invented in Silicon Valley doesn’t take too long to make it to Somalia, people from Colombia to Cambodia watch European soccer and listen to American music, and everything from political norms to religion flow across borders. I would say that the Four P’s capture these flows because products and people tend to be their vectors, but again I could be convinced otherwise. And if you think these categories deserve a P of their own, it just means that the Four P’s underplay the scale of global interconnection.

Why MAGA nationalism can’t succeed

In the eyes of MAGA nationalists and their far right cousins like the UK Reform Party, Germany’s AfD, or Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, much of the Four P’s should be stripped away. Bring the factories back home. Stop sending money for international aid projects or to international organizations. Stop letting so many people come across the border.

But life on our own would be immeasurably poorer than life together. A world without the global movement of products means Americans and Europeans living without coffee, bananas, and chocolate. A world without the movement of people means depriving ourselves of the world’s top minds and caregivers for our parents alike. A world without the movement of pollution isn’t even possible anymore—no wall will ever be big enough to keep the rest of the world’s greenhouse gases out of our part of the atmosphere, or vice versa. Without international complements, national-level governance is incapable of solving such a global problem.

In the rare instances when they need something from the world, right-wing nationalists think they can bully it out of them—a coerced minerals deal here, a drone strike on some alleged terrorists or cartels there, be ready to threaten astronomical tariffs until they agree to buy more of our stuff. This will work from time to time. Nothing says global interconnection will necessarily be fair, and those with more power are more likely to get their way.

But making domination a one-size-fits-all foreign policy approach is not just morally objectionable—as a long-term strategy, it is doomed to fail. Even the US, the most powerful country in the world, accounts for just 4% of the world’s people, 13% of its carbon dioxide emissions, and 26% of its economy. We are not strong enough to reserve all the benefits of global interconnection for ourselves. But in our positive-sum world—in a world where even the poorest countries are richer than the richest countries were two hundred years ago, and we are wildly richer than they could have ever imagined—we don’t need to.

Not all form of global interconnection will be equally beneficial. Not all will distribute the benefits as evenly. But whatever you do, you will be connected to the rest of the world. And however powerful you are, there is no way to single-handedly bend a modern world of eight billion people to your will. In the end, we’re all in this together.

AOB

Thoughts on the Four P’s? I think it’s a useful shorthand but I’m still working through it, so let me know what you think—what’s right, what’s missing, what are the perfect pertinent P phrases that I perplexingly passed on picking.

Central bankers agree rich countries need more immigrants: At the leading annual meeting of global central bankers, they raised a core economic risk: not enough immigrants. It’s a striking message to hear from a group that is far from far-left radicals. Derek Thompson also wrote a good piece on what a shrinking population means for the US.

Trying to fossilize the world: The Trump administration is committed to hitching the US to a dying, climate-destroying energy model. But it isn’t stopping there—the Trump administration is trying to drag other countries down with it through tariffs, threats, and potential attacks on a breakthrough to tax global shipping emissions.

The climate disasters we never hear about: I try pretty hard to keep up with global news on climate change, but even I am surprised by how many climate change-fueled disasters I miss. Just recently, 1,000 people were killed in a landslide in Sudan (which is already undergoing a brutal civil war). In Cape Verde, 1.5 times the annual rainfall of an island’s fell in five hours. Over 300 people killed in floods and landslides in Pakistan. 2,300 people killed across Europe in a heatwave. 78 people killed in floods in South Africa. (And while not linked to climate change, it is just so unfair that Afghans who have suffered so much were also hit with a major earthquake.)

Solar energy is great: But don’t forget that there is good climate news out there! This podcast episode with Chris Hayes and Bill McKibben on the amazing rise of solar will give it to you. And a very hopeful study found Africa’s imports of solar panels are skyrocketing.

India and China make up: After years of acrimony between India and China, Prime Minister Modi had a change of heart after Trump escalated tariffs on India and claimed that he was the key to preventing war between India and Pakistan. Modi and Xi Jinping—and 20 other global leaders—were chummy at the recent meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, where China announced new initiatives to deepen cooperation between member countries. A divided India and China limited the possibility of a global coalition that could counter the US—their newfound friendliness could be one of the most consequential shifts in global politics.

One good thing from the Trump administration: Plenty of caveats—that it should be more, that it’s the result of much-needed pressure on the administration over PEPFAR, that it needs to be delivered on—but the announcement that they will work to ensure two million people in poor countries get access to a breakthrough HIV-prevention drug by 2028 is a genuinely good move.

International aid remains at the vanguard of attacks on the separation of powers: The Trump administration is still determined to not spend much of the money Congress appropriated for international aid programs. Just as when USAID served as a trial run for abolishing a congressionally-authorized agency, recent complex legal maneuverings on international aid spending are determining whether Congress still holds the power of the purse. Good recent reporting from The Atlantic highlight one consequence of abruptly cutting aid programs—millions of dollars of supplies are wasted.

The Trump bump for aid can happen if we make it: Fascinating new public opinion research in Australia found that just giving people a 144-word article on the impact of US aid cuts led to more Australians saying the country gives too little aid than too much—something surveys had never found before. When people see all that is lost when aid investments are gone, they remember why these investments were so important in the first place. But that information isn’t going to make it to them on its own.