Everyone is misunderstanding what happened to USAID

I read 18 pieces reckoning with the end of USAID. Here's what they get wrong.

Every few weeks I come across a new piece in the now-popular think piece genre that is “USAID post-mortem / where do we go from here.” I remembered finding them frustrating, but I wanted to give them a fair shake, so I decided to read all of them I could find.

I read 18 in all: Zainab Usman, T. Alexander Puutio’s Stanford Social Innovation Review series, the Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network, Ken Opalo, Cindy Huang, George Ingram, W. Gyude Moore, Matt Yglesias, Santi Ruiz’s interview with Dean Karlan, Judd Devermont, William Harkewitz, Kevin Starr, and several Devex pieces (which heavily quote Daniel Runde).

And indeed, with a few exceptions, they generally suffer from a major flaw. It’s not that they were poorly written (I learned a lot). And it’s not that I disagree with them per se (I would like to see much of what they call for become reality).

The problem is that the development sector’s reckoning with the destruction of USAID has been largely unmoored from what actually happened. The post-mortems have tended to follow a similar recipe: a dash of lamentation and a spoonful of self-flagellation, topped with one cup of the author’s pre-existing policy preferences—all of which bear a tenuous relationship to what actually doomed USAID.

I read a lot of very smart people who struggled to process how dumb this all was, who foisted a technocratic framing onto what was fundamentally a political defeat to people who could not have cared less about impact evaluations and programmatic design.

Let’s go back to what actually happened (spoiler alert: it was democratic breakdown and rightwing culture war-radicalization), look at why many of the popular answers don’t check out, and then I’ll throw out a few thoughts for how to move forward.

What actually happened to USAID?

Remember what the world looked like on January 19. Developed countries’ foreign aid spending was facing headwinds and far short of needs, but it was nearly 50% higher than 2015 (though just slightly higher if you subtract COVID aid, Ukraine aid, and costs for refugees hosted domestically). There was no clear drop off visible in polling on foreign aid.

While there were good reasons to think USAID would take hits under Trump, no one was expecting it to be eliminated. The day after the election, Devex’s newsletter said that drastic cuts could be on the table, but it also said localization was “an intriguing bright spot.” And when people feared cuts, it was nothing like what ultimately happened. This wasn’t pollyannish: Project 2025’s main ask was to cut USAID funding to at least 2019 levels! Read that again: literal Project 2025 was envisioning a world where the Trump administration would cut six years of USAID funding growth, not even mentioning the possibility of eliminating USAID as an independent agency.

When Trump took office and DOGE went into USAID, even they didn’t plan on destroying it. But two weeks later, USAID was functionally dead. In the end, the administration terminated 83% of USAID projects, shuttered USAID as an independent agency, and kept on just 300 of USAID’s over 10,000 staff in the State Department.

Why do the sector’s popular answers not check out?

In reading all the reckonings, several common arguments emerged: USAID became insufficiently rooted in the national interest, USAID was insufficiently focused on economic growth, USAID failed to preserve its Republican allies, and USAID was insufficiently transparent and accountable. They all make some good points but have major flaws.

Wrong answer: USAID became insufficiently rooted in the national interest

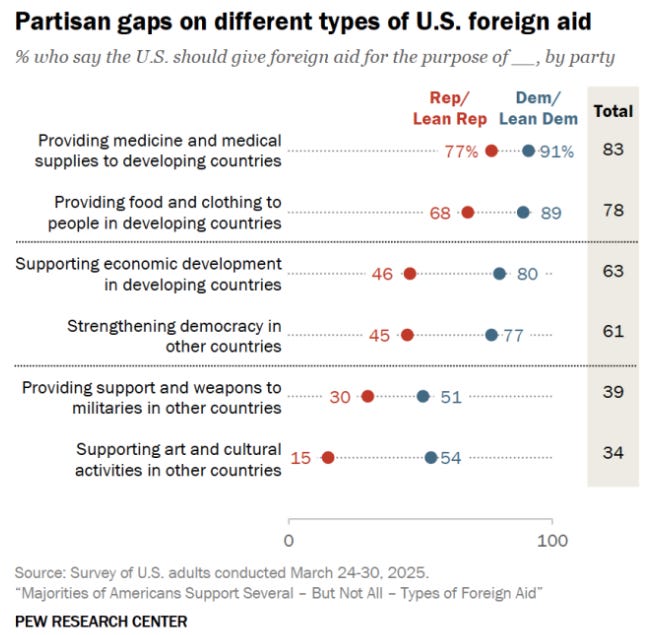

It’s understandable that many people reckoning with USAID’s destruction think it needed to better show its contributions to the national interest, because the Trump administration loves saying that’s what USAID failed to do. But this argument has several problems. For one, in polling on foreign aid (as shown below), the most popular uses of foreign aid are often those that are more morally-based and humanitarian, while foreign aid more closely-tied to power politics is relatively unpopular.

Note that medicine and food top the list

Military assistance is literally 13th out of 13!

And if prioritizing the national interest was really the Trump administration’s focus, we would see aid spending shifting towards cross-border challenges with spillovers that could rebound towards the US. But even though supporting the mitigation of emissions abroad spares Americans wildfires and floods, there might be no category of international spending Trump hates more. Ensuring migrants settle locally rather than continuing on to the US got a shout out in the State of the Union—when Trump was naming examples of wasteful government spending.

Why are were these categories of spending so targeted for the administration’s ire? Not because they don’t support the national interest, but because they’re on the wrong side of the culture war.

Wrong answer: USAID was insufficiently focused on growth

This one is framed in a couple different ways—growth, structural transformation, working ourselves out of a job—but the underlying point is the same: USAID didn’t do enough to move countries out of poverty. And it’s true that the historical path to prosperity has come when countries move up the value chain from commodity dependence and low-productivity agriculture to higher-value, diversified economic activities. Right now, many countries are just too poor to provide basic human needs.

But it is unclear what this has to do with the political dynamics that led to USAID’s destruction. Sure, MAGA World pointed out that aid hasn’t eliminated poverty—but it would be crazy to expect annual global aid equivalent to the GDP of New Zealand, a country of five million people, to catapult the five billion people who live on less than $4,000 per year into a life of prosperity.

And it is Charlie Brown with the football levels of credulity to believe this Trump administration when it says things like “trade not aid.” Remember, this is the administration started a global trade war with the idea that countries with trade surpluses with the US are cynically taking advantage of us. They have reserved many of the highest tariff rates for the countries that have been most successful with export-oriented industrialization. They more or less openly say that poor countries’ growth is a threat to American jobs and economic preeminence.

Wrong answer: USAID failed to preserve its Republican allies

Yes, it’s true that USAID needs Republican support if it is to be politically durable during swings of power, and it had much more Republican support in the days when George W Bush launched PEPFAR. But ask yourself this. What has changed more in the last 20 years: USAID's activities or the Republican Party? And the answer is clearly the latter. In George W Bush’s days, a dominant faction in the party was the Christian right, who I would have disagreed with on many things but genuinely believed in a global duty to promote human dignity. But in the two weeks that killed USAID, the central decision-maker was a guy whose formed his ideas on race in apartheid South Africa and launched an explicitly pro-Hitler chatbot. When nativist populism has become the Republican Party’s organizing principle, international programming focused on the global poor is just going to be a much tougher sell.

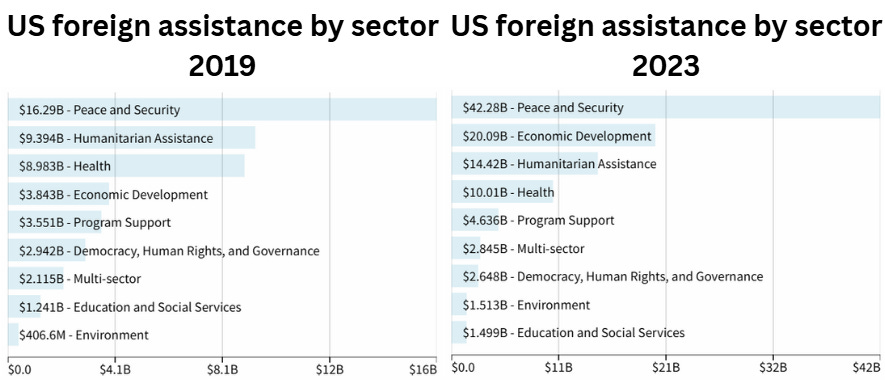

And it’s not true that USAID didn’t have Republican supporters. They insulated it from major cuts in Trump’s first term. Lindsey Graham was a vocal supporter. Marco Rubio was too! Of course, they could say that it wasn’t that they changed, but rather that USAID became a radical left-wing organization. But look at US foreign assistance spending by sector in 2019 and 2023 and say whether there was a drastic shift towards climate or other leftwing priorities.

What really happened is that the GOP became a cult of personality, and the man at the top (or at least the Rasputin in his ear at the vital moment) decided USAID should go. With the cost of bucking Dear Leader too high, Republican politicians fell in line.

Wrong answer: USAID was insufficiently transparent and accountable

A common refrain in the post-mortems has been that the development sector needs to adopt a laser focus on impact and transparency. There is the related point that USAID was too reliant on US-based contractors and procurement—something Elon Musk giddily took advantage of in claiming that only 10% of USAID payments made it to their purported destination, when in fact that stat meant that only 10% of USAID payments went directly to organizations in the developing world.

I am pro-localization and pro-transparency. But it isn’t really clear at all how these things would have protected USAID! Senator Moran of Kansas was one of the few Republicans to speak up for USAID. Why? Because Kansas farmers sell a bunch of food to USAID. Shifting towards local purchases of food would be far more development-friendly and cost-effective, but giving American farmers a direct interest in the continuity of US food aid creates a base of political supporters in red states. The concentration of USAID-related workers near DC meant there were people nearby to rapidly mobilize for rallies. (It’s also worth noting that the key barriers to localization are restrictions that Congress placed on foreign assistance.)

And on the transparency front, USAID was arguably the most transparent it had ever been. As they were destroying USAID, DOGE took down much of the publicly available data. The information was there, but DOGE had no interest in understanding it and was ready to call programs fraudulent just because they disagreed with them.

Still, one thing post-mortems like William Harkewitz, Cindy Huang, and George Ingram get right is that, even if USAID was relatively transparent, it was not easy to understand. Suppose an American who was a well-informed citizen but not a development specialist looked at the above list of programs that DOGE highlighted as wasteful and fraudulent. It’s very unlikely they would realize that male circumcision reduces AIDS, social cohesion in Mali is about preventing conflicts that facilitate recruitment for jihadist groups, and improving public procurement is—far from being a corrupt use of money—focused on preventing corruption. USAID was shrouded in technical jargon and there was almost no effort to market USAID to the American electorate, setting it up for failure in the comms war.

Right answer: USAID got sucked up into a vortex of culture wars and democratic breakdown

Rather than giving credence to the Trump administration’s talking points—that USAID didn’t support the national interest, or that it failed to promote economic growth—everything makes much more sense when you put its destruction through the lens of the culture war. If you wanted USAID to be more closely tied to US foreign policy priorities, as the administration claims, you would think they would want it to undermine leaders the US opposes. Indeed, the idea that USAID was a neocolonialist instrument was a common far-left complaint. But somehow it was far-right MAGA World who became obsessed with this. Why? Because they became convinced that USAID was part of a globalist conspiracy to support color revolutions—which is how they see the 2020 election.

USAID was by no means widely reviled in the US population, but X amplifies far-right fringe voices like Mike Benz (who Elon Musk retweeted many times during the vital two weeks), and the guy who runs X just so happened to be leading DOGE. The culture war framing also explains why, after the destruction of USAID, Marco Rubio made a stink about declaring that “where there was once a rainbow of unidentifiable logos on life-saving aid, there will now be one recognizable symbol: the American flag.” Recipients deserved to know that the aid was “an investment from the American people,” Rubio said. This is, obviously, senseless posturing to the base. Look at USAID’s old logo below—how was anyone supposed to know it came from the American people???

All the normal democratic checks that could have stopped this far-right fringe were out of operation. Congress was completely cut out, and even Republican members of Congress who privately supported USAID were terrified to criticize the head of the party’s cult of personality. Lawsuits moved far too slowly and had to make it through a judiciary that leans heavily to the right. A key node in the information ecosystem was owned by the head of DOGE. Everything was left to Pete Marocco and a few DOGE boys who misunderstood the most basic facts about USAID.

The abolition of a congressionally-authorized agency—which legally cannot be eliminated by the executive—would normally be an extended process with plenty of time for the agency’s supporters to push back. But in this state of democratic breakdown, USAID could be virtually eliminated within two weeks. Because pro-development actors only had weak organizing infrastructure to draw on, serious organizing didn’t start until USAID was already functionally dead.

And for anyone in the development community who would draw on excessively insular explanations, let’s remember a very similar thing happened to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

So where do we go from here?

There are real dangers to coalescing around false interpretations of what happened: prioritizing policies that are sub-optimal from a development perspective because they are perceived as political necessities, giving undue credence to the idea that US support for development is politically unviable, and missing opportunities for political durability whenever the opportunity to reconstruct US development policy re-emerges. (In many ways, the European cases of declining aid are quite a bit more instructive than the highly idiosyncratic destruction of USAID.)

Because I noted my wariness of people using USAID’s destruction to justify their pre-existing preferences, I should put my cards on the table. I think foreign aid has been incredibly effective (if still flawed) for things like public health and basic education, and there are very few practical substitutes for humanitarian emergencies. I would like to see much more localization and more budget support direct to governments. I think addressing the gross deprivation of human dignity and waste of human potential caused by global poverty—and addressing shared global crises like climate change, pandemics, and demographic shifts—requires much more ambitious development policy than anything the US has done in recent years.

I also think that aid is just one of the many ways the US and other rich countries influence global development—debt/finance, trade/investment, climate change, immigration, and international tax policy all have equal or greater impacts. I am interested in how we remember what happened to USAID because it matters, but I am also interested because many of the same dynamics play out in that broader suite of issues.

What does an accurate account of the destruction of USAID teach us? The most important thing is that much of what dictates the future of US development policy is outside the scope of the insular technical debates development experts are used to having. The far more decisive issue is how we proactively build the base of political support needed for high-quality US development policy. With that mindset, here are three key principles:

We need to defeat the zero-sum nationalist view of the world: There will be those who want development to stay in its lane and triangulate to the current political equilibrium, to frame things in a way the America First people can accept. But they are just not going to buy it. When a worldview glorifies national domination, thinks cooperation is for suckers, and sees people in poor countries as disposable and sub-human, its adherents aren’t going to have a place for policies that support development in the Global South. Our cause hinges on the prevalence of a worldview that can at least accept that mutual beneficial cooperation between countries is possible, that our moral obligations don’t take a hard stop at the border, and that people everywhere deserve respect and decent lives. That doesn’t need to be partisan—a large majority of Americans believe it and I think there are Republican elites who do too—but the Trump administration and their rightwing nationalist allies around the world don’t.

It’s a communications war—we need to be in it: It’s worth thinking about why PEPFAR has survived better than almost all other foreign aid (while still taking hits that have already killed people). It helps that it was started by a Republican, but more than anything it is because PEPFAR is the most easily communicable thing USAID does: “the US has saved 25 million lives from HIV/AIDS and if people stop getting their medicine they will die.” Boom. One sentence. Development is complicated, but we should be able to package anything that could be politically contentious in a 1-2 sentence justification. Outcome-based initiatives (like PEPFAR, or the World Bank/AfDB’s Mission300 to connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030) are going to be easier to communicate. And once there’s a strong message, it actually needs to be pushed out—and not just through stale press releases and stuff that sounds like it went through three layers of review. Philanthropies need to put serious money behind advocacy and communications. Scrap the Smith-Mundt Act if needed. Stop bringing logframes to a meme fight. In the last few months, there have been successful startups providing models of pro-aid comms: Friends of USAID, USAID Stop-Work, The Last Mile with USAID, and more. The tragedy is that so little of this existed when it was most needed.

US development policy needs to be embedded in American society: In those vital two weeks, the most organized and engaged group of Americans paying attention to USAID were far-right conspiracy theorists who wanted to destroy it. It’s not that Americans supported such a drastic move, but rather that not that many Americans showed up for USAID, especially Americans without professional ties to it. Global development policy’s biggest political challenge is not that it is unpopular but that it is invisible. As you can read about in my piece below, I think a 20% bump in the general public’s support for international development investments would accomplish less than getting 1% of the population to a place where they might realistically call their congresspeople, show up to a rally, or vote on it. Ideally that 1% would be somewhat demographically, geographically, and politically diverse. One piece of achieving this could be making compromises on localization (especially on food aid) and making sure qualified faith-based implementers get a healthy share of contracts, but it’s much more than that. Expand technical assistance programs that directly put Americans (not just full-time development professionals) into direct contact with people in developing countries. Fly influencers out to see the impact of US development investments. As turbocharged US development communications begin to reach Americans, make sure there’s an organizing pathway available to them. Yes this will be hard, yes this will take money, yes it will make some experts cringe. And yes, it is deeply unfair that the world’s less fortunate are excluded from the rich world’s bounty, and that their access to even a small cut of it hinges on the acquiescence of those lucky enough to live within the rich world’s gates. But at least for now, that’s the world we live in.

Most people don't care about your issue

·A pretty intuitive way to think about politics is to think about the general public’s views on political issues. In a democratic society, public policy should be downstream from voters’ opinions. So if there’s a policy you want to change, you should try to get the general public to support that change.

AOB

If you liked this post and want to read more, the best way to do so is to subscribe!

PEPFAR is amazing: In the strategic and analytical thinking on USAID, it shouldn’t get lost what a human tragedy it is to throw away the very real things USAID has achieved. This chart on the impact of PEPFAR in Eswatini is just staggering.

Tooze on development: I’m late to it, but this Adam Tooze lecture on “Sustainable Development and the Crisis of US Hegemony” is well worth a listen. It covers the mega-trends of development, China’s staggering transformation, and the weaknesses of the SDG agenda (even if I’m more optimistic than him). He also did a podcast episode on the state of global development.

The impact of aid cuts and tariffs: ODI did really interesting research on how aid cuts and tariffs are likely to affect different countries. Here’s a useful summary chart.

Zero-sum nationalism is hitting Americans’ wallets: It turns out trying to cut ourselves off from the rest of the world might not be such a good idea. Tariffs and the immigration crackdown are starting to raise prices and slow down the US economy.

Free DC: As you might know, I have lived in Washington DC for the last three years. I have found it a wonderful place to live, have never been the victim of crime, and can only remember a handful of times I felt even marginally unsafe. But now, I know that any time I step outside the house I could run into masked men in unmarked vehicles seeking to kidnap my neighbors. It’s an authoritarian power grab that is possible because Washington DC has been denied the statehood it deserves. I have felt a real sense of strength and community in seeing neighbors come together to stand against this, and I encourage people to plug in to groups like Free DC.

I'm really glad you wrote this and completely agree. In generally, the destruction of USAID was idiosyncratic and horrible. Driven by weird conspiracy-minded cultists. There wasn't much of a theory behind it, and it doesn't reflect pre-existing policy or trends. I wrote a few pieces on the same theme, although not argued as well as you do. I also think that we shouldn't give up on USAID and foreign aid in general. Even though there have been huge set backs, we can recover a lot of things without "reimagining aid" or any new institution-building. For one - USAID hasn't been dismantled legally. It's still not totally clear that the courts will approve this destruction or that Congress will abide. We can still fight that. It's a gawd awful mess, and but that specific question hasn't been disposed of. Second, there remains a strong reservoir of support for aid - especially the health and humanitarian - in congress, among republicans, etc. We can build on that and hold rubio/lewin/trump accountable. And doing that now rather than waiting for months or years means saving lives in the short term.

This piece is superb. Piece after piece attempts to figure out what the victim—USAID and its beneficiaries—did to deserve what happened. It can’t be explained that way